The Great (Immigration) Pause Is The Path To National Cohesion

12-Minute Audio Podcast Review of This Article

6-Minute Video Summary of Article

Preamble

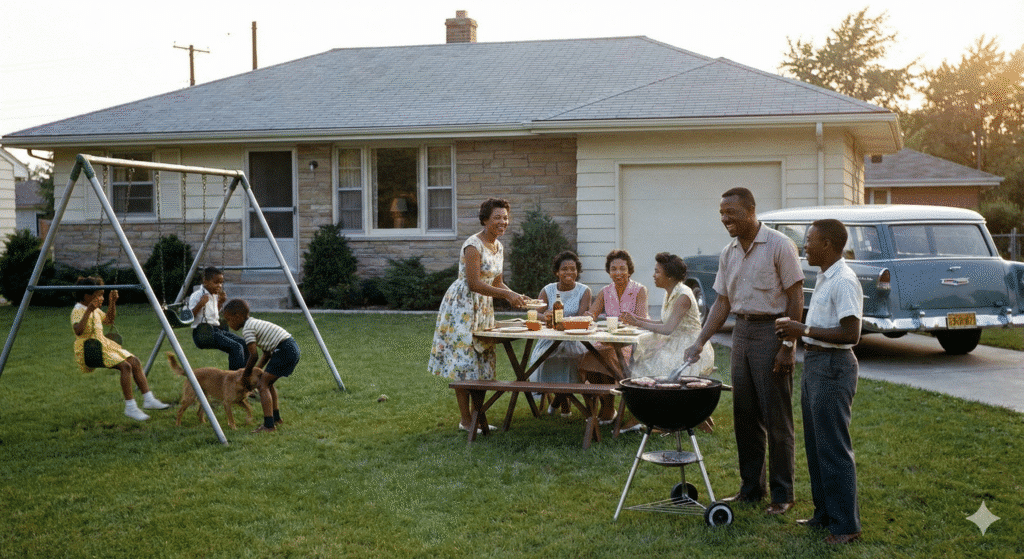

I graduated from high school in 1971 and from college in 1974 with my Bachelor’s Degree. At that time, the foreign-born population of the USA was only about 4.7% and regardless of political party, there was not a massive division in this country of one party pitted against the other. At least it wasn’t as severe, the opposing viewpoints where not as starkly different as they are today, and the level of hatred between Left and Right political views did not rise to the intensity we see in the modern era.

In fact, there was so much unity that it was unthinkable for an average American of either of the major parties to believe that socialism and communism were somehow “good”, that boys can become girls or that capitalism was responsible for poverty and misery. Regardless of party, we were all AMERICANS and we all held many very important beliefs in common.

Fast-forward to the present time, near the end of 2025 when I posted this article, and we literally witness hatred between the two major political parties. It’s Left against Right everywhere you turn. On the Right side are those who are trying to preserve our unique American heritage, culture and most of all, our liberties. By “liberties” I mean freedom from dependency on government, a very limited role of government in our lives, and the fact that government should have little if any intervention in our lives; and government certainly does not “OWE” us anything as individual Americans.

On the other, is the political Left, who generally believe government’s primary role is to take care of people from cradle to grave, to ‘rule’ rather than lead, that the masses should look to government for solutions to their problems rather than individuals being responsible to solve their own issues. Leftists believe it’s better for government to intervene in our lives at every turn.

In short, the Right believes as our Founding Fathers did, that a limited government enables and promotes true liberty and freedom. It’s not easy. But it’s worth it. The Left believes in large government and ensuring the citizens are dependent on that government for nearly every aspect of their lives.

These two competing visions are ripping the United States of America apart like never before. It was preventable. And it’s still curable. Today I’m outlining a course of action with a proven track record to restore a cohesive social order and the type of liberty that was, in my younger years, common place in America.

Before researching, curating, writing, editing and publishing this article, I produced another one. That one is also heavily documented and researched. It’s called “The Immigration Pause of 1924-1965: A Foundation for American Unity and Prosperity.” It’s published as a PDF and was intended originally for only a few of my close friends and colleagues. But it’s a foundational work and is broadly cited in this article so I thought it only appropriate to make the entire article available in its original PDF version for you here.

By the 1950s and 1960s, most Americans had shed their hyphenated-American labels, like Italian-American, German-American, etc. Indeed, one of the most common phrases I used to hear (and often repeated) as I was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s was “IT’S A FREE COUNTRY!” Today, I never hear phrase anymore in personal or public discourse. That should tell us ALL something about how quickly our precious liberties are slipping away.

In this article, I’m setting forth my belief that the United States MUST return to a policy of limited immigration similar to what we had during The Great Pause. This is the only way the USA is going to return to a cohesive, united society and FREE (as defined by our Founding Fathers) and peace-loving society. The immigration restrictions must be consequential and cannot be race-based as they were at the beginning of the Great Pause.

Will extremely limited immigration solve all our problems as a society? NO! But it’ll solve a lot and provide the framework for better-resolving the issues and problems of a cohesive society who understand that their government operates ONLY from the consent of the governed. Membership in this great nation is a privilege, not a right.

The principles I espouse below have the power to unify America as never before. We can truly restore The American Dream for the vast majority of us citizens who call the United States “home”, and unify our country under the banner of liberty, limited government, and freedom from government dependency and control, just as as our Founders provided for us.

Introduction

The history of the United States is frequently distilled into a simplified narrative of continuous, open-door migration—a “nation of immigrants” continuously revitalized by new arrivals. However, a rigorous examination of the historical record reveals that America’s most cohesive, prosperous, and socially unified era was forged not by open borders, but by a deliberate, four-decade period of immigration restriction.

Between 1924 and 1965, the United States operated under an immigration policy known to historians and demographers as the “Great Pause.” This era, bookended by the Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act) and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Act), represents the most consequential exercise of congressional plenary power over the nation’s demographic destiny in its history.

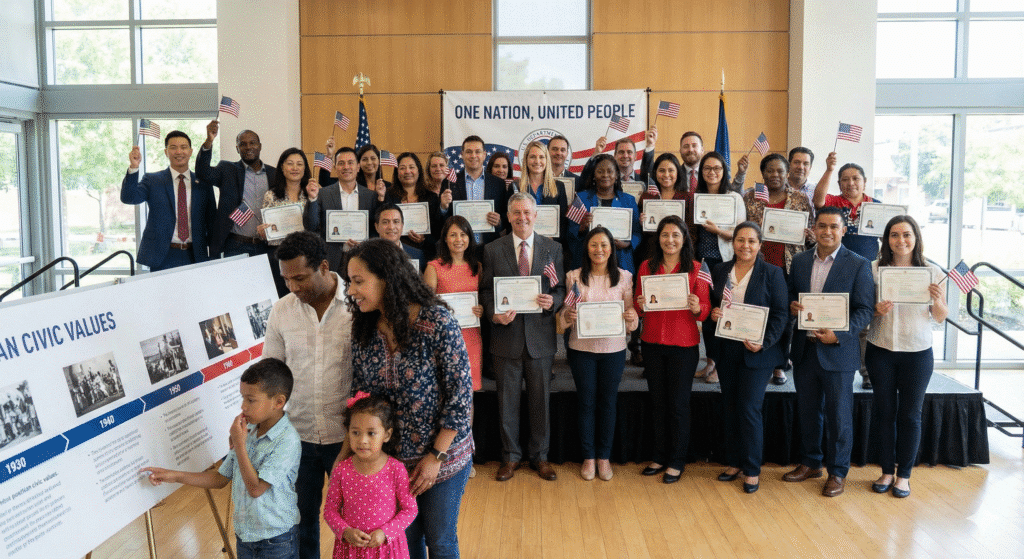

Far from being a period of stagnation or isolationism, the Great Pause facilitated the successful assimilation of the more than 20 million immigrants who had arrived during the “Great Wave” of 1880-1920. By dramatically limiting the inflow of new arrivals, the legislation allowed the “melting pot” to actually function, transforming disparate, linguistically isolated ethnic enclaves into a unified American citizenry bound by a shared language, culture, and constitutional allegiance.

Economically, the restriction on the labor supply catalyzed one of the most profound periods of wage growth in American history, creating the modern middle class and, most significantly, opening the doors of industrial opportunity to African Americans. During this period of tight labor markets, the real earnings of Black men rose by over 400%, a feat of economic justice achieved through market forces rather than government redistribution.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the legislative mechanisms, statistical realities, and cultural consequences of the Great Pause. It argues, through the lens of constitutional conservatism and originalist principles, that a cohesive citizenry—united by an unreserved embrace of the American experience, laws, and history—is the indispensable bedrock of limited government and individual liberty.

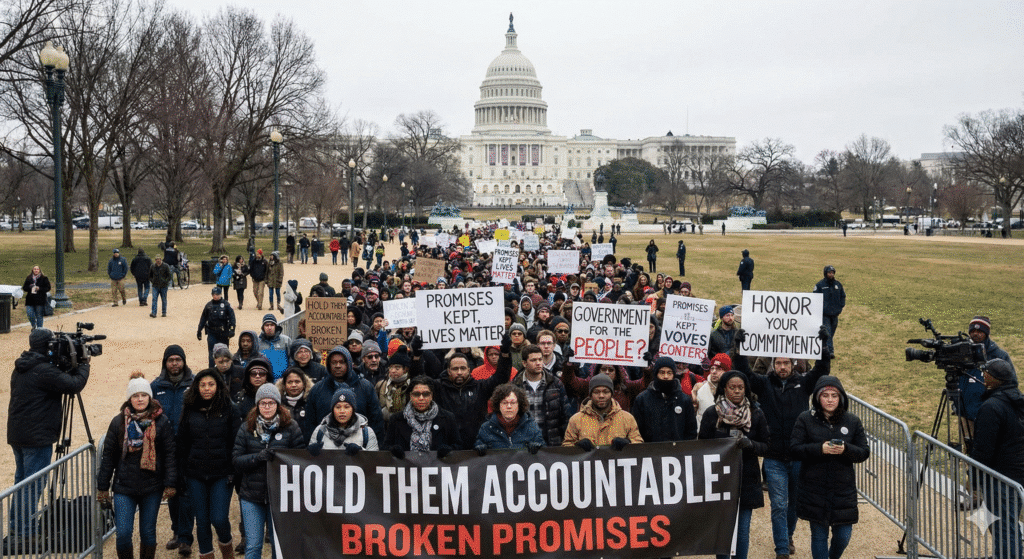

The abandonment of these principles in 1965, based on “broken promises” regarding demographic stability, has led to the erosion of social trust, the fragmentation of national culture, and the expansion of the administrative state—confirming the warnings of thinkers from George Washington to Milton Friedman that a free society cannot survive without a shared social compact.

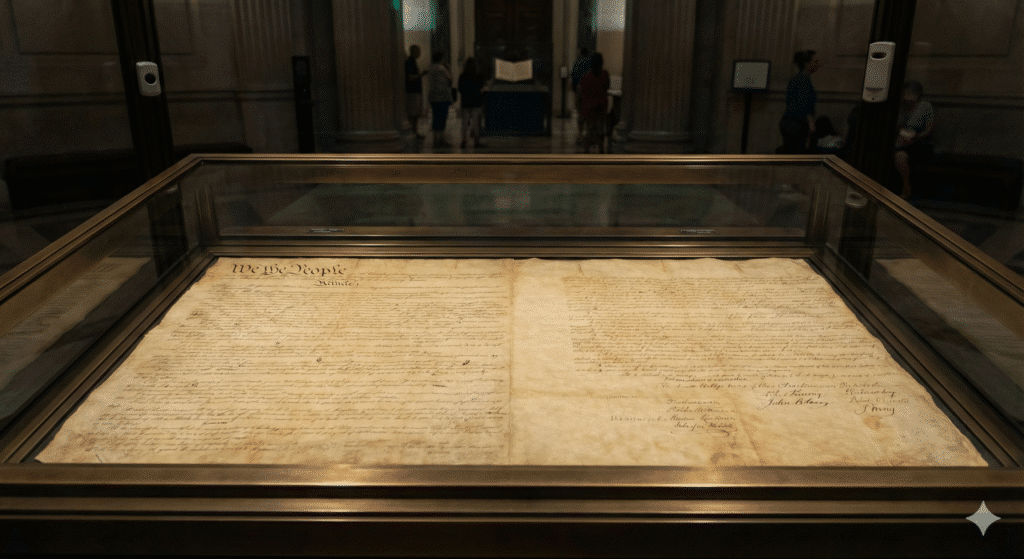

The Constitutional Foundation of Immigration Control

To understand the legitimacy and necessity of the 1924 legislation, one must first ground the discussion in the constitutional framework envisioned by the Founding Fathers. The modern conservative argument for immigration restriction is not an innovation but a return to the original understanding of the American social compact.

Sovereignty and the Social Compact

The United States Constitution established a specific type of government: a constitutional republic, rooted in commercial freedom, designed to secure the blessings of liberty for “We the People” and their “Posterity.” It was not designed as a universal abstraction open to the entire world, but as a concrete political community with defined membership.

The Founders understood that a republic, unlike an empire, requires a high degree of social cohesion. An empire can rule over disparate, disconnected tribes through force; a republic relies on the voluntary cooperation of a people who see themselves as part of a shared enterprise. This concept is rooted in the Social Compact theory—the idea that citizens consent to be governed in exchange for the protection of their rights and the preservation of their distinct political community.3

Thomas Jefferson, in his Notes on the State of Virginia, expressed deep skepticism about the importation of foreigners who might not share the republican principles of the young nation. He feared that immigrants from absolute monarchies would “bring with them the principles of the governments they leave, imbibed in their early youth; or, if able to throw them off, it will be in exchange for an unbounded licentiousness, passing, as is usual, from one extreme to another“.4 Jefferson argued that such a heterogeneous population would render the legislation a “heterogeneous, incoherent, distracted mass,” incapable of the unified action required for self-government.

Alexander Hamilton, often viewed as the more cosmopolitan Founder, shared this concern. In 1802, he wrote, “The safety of a republic depends essentially on the energy of a common national sentiment; on a uniformity of principles and habits; on the exemption of the citizens from foreign bias, and prejudice; and on that love of country which will almost invariably be found to be closely connected with birth, education, and family“.6 Hamilton warned that the influx of foreigners would “change and corrupt the national spirit,” a corruption he viewed as fatal to republican liberty.

Plenary Power and the “One People” Ideal

The Constitution grants Congress the power “to establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 4). This enumerated power, combined with the inherent sovereign right of self-preservation, forms the basis of the Plenary Power Doctrine. The Supreme Court has consistently held that the power to exclude aliens is a fundamental sovereign attribute exercised by the government’s political departments, largely immune from judicial control.7

The goal of this power was not merely to manage numbers but to forge a unified people. George Washington, in a letter to John Adams, articulated the ultimate standard for successful immigration policy: “by an intermixture with our people, they, or their descendants, get assimilated to our customs, measures, laws: in a word soon become one people“.8

This phrase—“one people”—is crucial. It implies that the end state of immigration must be the dissolution of foreign allegiances and the complete adoption of an American identity. The Founders did not envision a “multicultural” society of competing groups, but a unified citizenry where ethnic origins were secondary to civic allegiance. The “Great Pause” of the 20th century was the legislative fulfillment of this Washingtonian ideal.

The Crisis of the Great Wave (1880-1920)

To appreciate the necessity of the 1924 restrictions, one must examine the demographic shock that preceded them. Between 1880 and 1920, the United States experienced the “Great Wave” of immigration, a mass migration event that tested the limits of the nation’s absorptive capacity and threatened the social cohesion necessary for limited government.

When reading this section, compare what has happened during the past 60 years to the Great Wave. In the past 60 years, we’ve experienced a nearly uncontrolled immigration, including both legal and illegal immigrants. So historically speaking, the USA simply resumed The Great Wave but in even greater numbers. The realization of what we have done to ourselves in these past 6 decades is truly sobering.

The Scale of the Influx

The sheer volume of immigration during this period was unprecedented. From 1880 to 1920, approximately 23 million immigrants entered the United States (see Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2014). Immigrant America: A Portrait (4th ed.). University of California Press). In the single decade between 1900 and 1910, the country absorbed nearly 9 million people.

By 1910, the foreign-born population reached 14.7% of the total U.S. population, a historic peak.1 To put this in perspective, this percentage is higher than the foreign-born share during the height of the Irish potato famine immigration in the 1850s.

This wave was distinct not just in volume but in origin. Unlike the previous waves from Great Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia—nations with cultural, religious, and political traditions relatively similar to the American founding stock—the “New Immigration” hailed primarily from Southern and Eastern Europe. Italy, Russia, Poland, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire became the primary source countries. In the peak years of 1900-1914, Italian immigration alone averaged 210,000 annually.1

The Failure of Assimilation and “Hyphenated Americanism”

The massive influx overwhelmed the informal and formal mechanisms of assimilation. By 1910, census data revealed a startling lack of integration.

Twenty-three percent (23%) of the 13 million foreign-born residents over age 10 – roughly 3 million people, could not speak English. In major industrial centers, entire neighborhoods functioned as foreign colonies. In Cleveland’s Mayflower School, for instance, the majority of students were from Czech families, and assimilation into English was slow and painful.

This fragmentation became a national security crisis with the outbreak of World War I. The specter of “hyphenated Americanism”—citizens who split their loyalty between the U.S. and their ancestral homelands—haunted the political discourse. Former President Theodore Roosevelt famously declared in 1915, “There is no room in this country for hyphenated Americanism… The one absolutely certain way of bringing this nation to ruin, of preventing all possibility of its continuing to be a nation at all, would be to permit it to become a tangle of squabbling nationalities“.8

The “Americanization” movement, launched by both government and private organizations like the YMCA and Ford Motor Company, attempted to speed up assimilation through English classes and civics instruction.10 However, as historians have noted, these efforts were “brief, unevenly applied,” and ultimately insufficient against the tidal wave of new arrivals.1 As long as the ports remained open, the “melting pot” could not build up enough heat to fuse the disparate elements into a single alloy.

The Collapse of Social Trust

The era also saw the importation of radical political ideologies alien to the American constitutional tradition. Anarchism, syndicalism, and Bolshevism found fertile ground in the unassimilated immigrant enclaves of industrial cities. The bombings of 1919, carried out by Italian anarchists, confirmed the fears of many Americans that unrestricted immigration was importing not just labor, but revolution.

By 1920, a consensus had formed across the political spectrum: the nation was “saturated.” The social capital required for a high-trust society was eroding. To save the republic, the gates had to be closed.

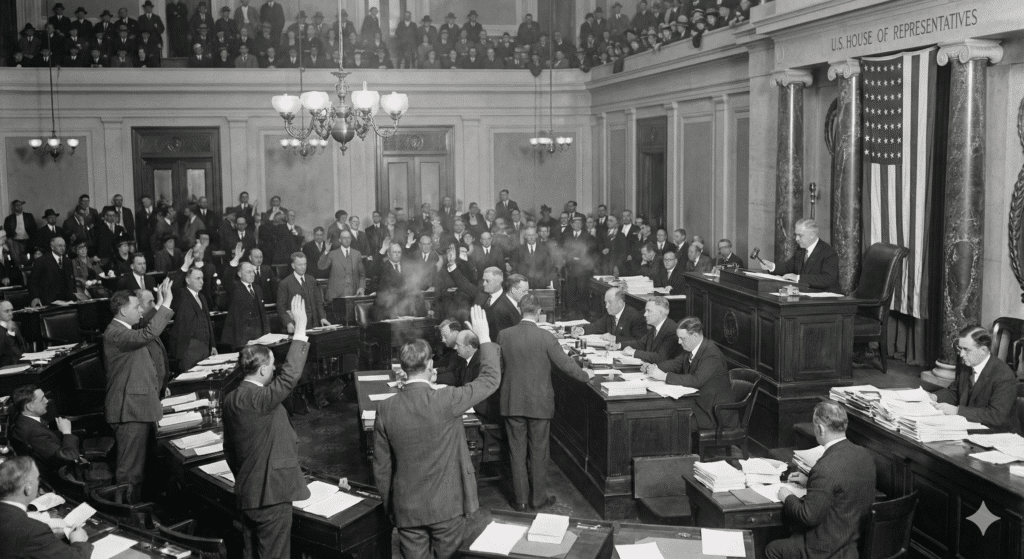

The Legislative Architecture of Restriction

The response to this crisis was the construction of a rigorous legislative regime designed to halt mass immigration and restore the nation’s demographic stability. This was not a hasty reaction but a deliberative process involving three major acts of Congress.

The Emergency Quota Act of 1921

The first major step was the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, signed by President Warren G. Harding. This law represented a paradigm shift, introducing the first numerical limits on immigration in U.S. history.11

Key Provisions:

- National Origins Quota: The Act restricted the number of immigrants from any country to 3% of the residents from that country living in the U.S. as of the 1910 Census.

- Total Cap: It set an annual ceiling of approximately 357,802 immigrants from outside the Western Hemisphere.1

Impact

The effect was immediate. Immigration dropped from 805,228 in 1920 to 309,556 in the 1921-1922 fiscal year.1 However, restrictionists argued that the 1910 census baseline was too recent; it locked in the demographic shifts of the Great Wave rather than reversing them. They sought a more permanent and restrictive solution.

The Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act)

The definitive legislative achievement of the era was the Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act. Signed by President Calvin Coolidge on May 24, 1924, this law codified the principle that the U.S. government had the right and duty to curate the composition of the citizenry to ensure the survival of American institutions.

Key Provisions and Mechanics:

- Tightened Quotas: The Act reduced the annual quota from 3% to 2%.12

- Changed Baseline (The 1890 Census): Crucially, the Act shifted the baseline for the quotas from the 1910 census back to the 1890 census.13 This was a deliberate strategic choice. By using 1890—prior to the bulk of the Southern and Eastern European influx—the law heavily favored immigrants from Great Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia. These groups were viewed as having higher “assimilability” and a closer cultural affinity to the nation’s founding stock.

- Overall Cap: The total annual quota was slashed to approximately 165,000, and later reduced further to 150,000 in 1927.13

- Consular Control System: The Act established the modern visa system. Prospective immigrants were now required to apply at U.S. consulates in their home countries rather than arriving at Ellis Island and hoping for admission. This “remote control” gave the U.S. government proactive authority over its borders.13

- Border Patrol: The Act authorized the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol, acknowledging that restrictive laws required enforcement machinery.13

Philosophy of the Act:

Senator David Reed of Pennsylvania, the bill’s co-sponsor, was explicit about the law’s intent. He declared that the law ensured “The racial composition of America at the present time thus is made permanent”.(1) While modern observers rightly criticize the eugenicist language often employed by restrictionists of this era, the core political objective was the stabilization of the national culture.

President Coolidge summarized the constitutional conservative view in his 1923 State of the Union address: “New arrivals should be limited to our capacity to absorb them into the ranks of good citizenship. America must be kept American“.15 This was an assertion that the American political order was not a generic operating system that could run on any hardware, but a specific cultural inheritance that required protection.

Statistical Impact: The “Great Pause” Begins

The 1924 Act succeeded in its primary objective: it stopped mass immigration cold.

Table 1: The Collapse of Immigration Inflows (1920-1929)

| Year | Annual Immigration | Context | Source |

| 1920 | 805,228 | Post-WWI Surge | 1 |

| 1921 | 560,000 | Pre-Restriction | 1 |

| 1922 | 309,556 | Impact of 1921 Emergency Act | 1 |

| 1924 | 706,896 | Rush before 1924 Act takes effect | 1 |

| 1925 | 294,000 | Immediate Impact of Johnson-Reed Act | 1 |

| 1929 | 280,000 | Stabilization | 1 |

The drop was precipitous. Total immigration fell by 58% in a single year (1924 to 1925). Immigration from targeted nations collapsed even further; Italian immigration fell from an average of 210,000 (1900-1914) to a capped quota of roughly 4,000 per year—a 98% reduction.1

This initiated a 40-year period where the U.S. admitted only 7.3 million immigrants total—roughly one-third of the number admitted in the previous four decades. The foreign-born share of the population began a steady, inexorable decline:

- 1910: 14.7% (Peak)

- 1920: 13.2%

- 1930: 11.6%

- 1940: 8.8%

- 1950: 6.9%

- 1960: 5.4%

- 1970: 4.7% (Historic Low) 1

This 4.7% figure in 1970 represents the nadir of “foreignness” in American society—a moment when the American population was more culturally unified than at any point since the early republic.

The Crucible of Assimilation: Unity Through Restriction

The “Great Pause” was not merely a negation of entry; it was a positive program of nation-building. By turning off the tap of new immigration, the U.S. government forced the massive immigrant population already present to look inward to America rather than backward to Europe. The 40-year respite provided the necessary “time and space” for the sociology of assimilation to do its work.

The Mechanics of Assimilation

Without the constant replenishment of new arrivals to maintain the linguistic and cultural isolation of ethnic enclaves, these communities naturally began to disintegrate and integrate into the broader society.

- Language Acquisition: The decline in new non-English speakers increased the utility and necessity of learning English. By the 1950s, the thriving foreign-language press of the 1910s had largely withered or transitioned to English. The percentage of the foreign-born who could not speak English dropped precipitously as the population aged and acculturated.1

- Intermarriage: This is the ultimate metric of assimilation. As the supply of potential spouses from the “old country” dried up, immigrants and their children increasingly married outside their specific ethnic group. Research analyzing census data from this period shows a marked increase in exogamy (marrying out) among second and third-generation European immigrants.16 The distinct “Italian” or “Polish” identity began to merge into a broader “Catholic” or simply “American” identity.

- Socioeconomic Convergence: Perhaps the most striking success was economic. A study comparing twelve ethnic groups in 1910 and 1980 found that by 1980, ten of the twelve groups displayed uniform mean socioeconomic index scores. The “duration in the host society”—enabled by the pause—was the critical variable. The pause allowed the children of the Great Wave to move out of the tenement, into the suburbs, and up the economic ladder without facing competition from a new wave of low-skilled arrivals.1

Forging National Unity in Crisis

The assimilation achieved during the Great Pause was not a luxury; it was an existential necessity. The United States faced two existential threats in the mid-20th century: the Great Depression and World War II.

The cohesion forged by the immigration restriction allowed the nation to weather these storms as a unified people. When the United States entered World War II, it did not do so as a collection of “squabbling nationalities,” but as a singular national entity. The draft boards of 1941 did not face the same crisis of “divided loyalties” that plagued the nation in 1917. The sons of Italian, German, and Jewish immigrants fought simply as Americans.

This unity was the fulfillment of George Washington’s vision: “by an intermixture with our people, they, or their descendants, get assimilated to our customs, measures, laws: in a word soon become one people“.8 The Great Pause proved that assimilation is a function of numbers and time; by controlling the former, the nation bought the latter.

The Golden Age of the African American Worker

For the constitutional conservative, the economic lesson of the Great Pause is clear: limited government and free markets work best when the labor supply is not artificially inflated by mass migration. The restrictionist era coincides with the most robust period of broad-based prosperity in American history, specifically for the most marginalized group: African Americans.

The Economics of Labor Scarcity

The economic logic of the 1924 Act is rooted in the law of supply and demand. As Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson noted in his seminal textbook Economics (1964): “By keeping supply down, immigration policy tends to keep wages high. Let us underline this basic principle: Limitation in the supply of any grade of labor relative to all other productive factors can be expected to raise its wage rate”.1

Prior to 1924, Northern industrialists had little incentive to recruit Black workers from the South or to improve wages; they could simply send agents to Europe to recruit low-wage laborers. Economists Timothy Hatton and Jeffrey Williamson estimated that in the absence of mass immigration after 1870, the urban real wage would have been 34% higher by 1910.1

The Great Compression and Black Progress

When the Immigration Act of 1924 cut off the supply of European labor, the dynamic changed overnight. Employers, desperate for labor to fuel the roaring industrial economy, were forced to look domestically. This triggered the Great Migration of African Americans from the stagnant agrarian South to the booming industrial North.

The resulting wage growth was staggering. Economists have concluded that from 1940 to 1970—the period directly corresponding to the immigration pause—the average real earnings of White men rose by 210%. But for Black men, real earnings rose by an extraordinary 406%.1

Table 2: Real Wage Growth During the Immigration Pause (1940-1970)

| Demographic Group | Real Earnings Growth |

| White Men | +210% |

| Black Men | +406% |

This era is often called the “Great Compression” because the gap between the rich and the working class shrank dramatically. This was not achieved through welfare payments or socialist redistribution, but through the market mechanism of labor scarcity. By restricting the importation of cheap labor, the government empowered the American worker—Black and White—to command a higher price for their toil.

Civil rights leaders of the era understood this. Figures like A. Philip Randolph and W.E.B. Du Bois consistently argued that mass immigration was detrimental to the economic advancement of Black Americans. The 1924 Act, despite its flawed “national origins” rationale, was functionally the greatest anti-poverty program in African American history.

The “Broken Promises” of the 1965 Act

The era of the Great Pause ended not because of economic failure, but due to a political shift that prioritized abstract ideology over national interest. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Act) dismantled the national origins quotas and set the stage for the current era of mass migration. Crucially, it was passed based on a series of explicit assurances to the American people that it would not alter the nation’s demographic or cultural fabric—assurances that history has proven to be catastrophically false.

The False Assurances

Proponents of the 1965 Act, operating in the context of the Civil Rights movement, argued that the national origins quotas were an embarrassing relic of racism. However, they vehemently denied that abolishing them would lead to mass immigration.

- Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA), the bill’s floor manager, famously promised: “The bill will not flood our cities with immigrants. It will not upset the ethnic mix of our society. It will not relax the standards of admission. It will not cause American workers to lose their jobs“.18

- President Lyndon B. Johnson, at the signing ceremony beneath the Statue of Liberty, declared: “This bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives“.19

- Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy testified that he expected immigration from the Asia-Pacific triangle to be approximately 5,000 in the first year and then “virtually disappear“.20

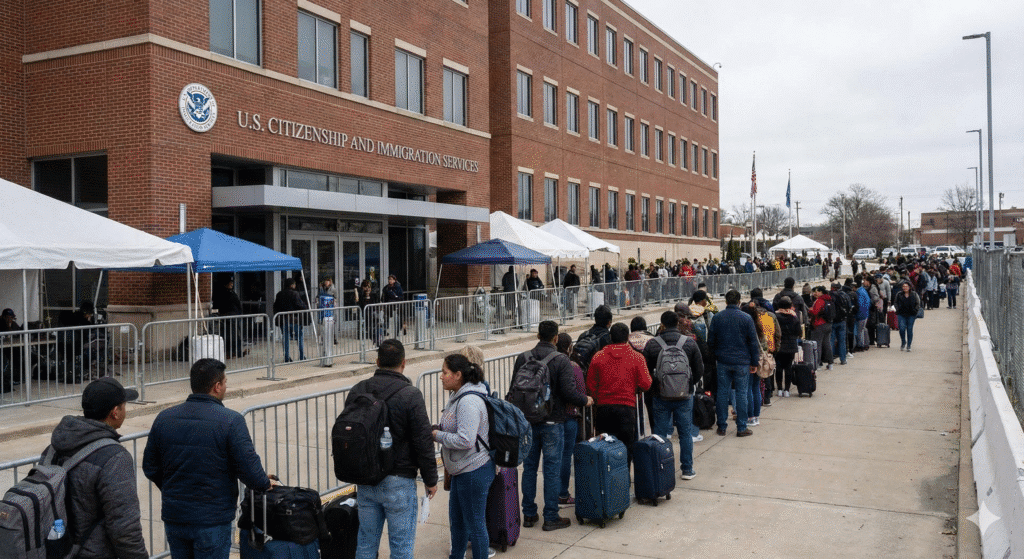

The Mechanism of Unintended Consequences

These promises were nullified by the structural changes within the bill. While the Act abolished the discriminatory national origins quotas, it replaced them with a system that prioritized family reunification (chain migration) over skills or national need.21

This created a self-perpetuating machine for exponential growth. A single immigrant could sponsor their spouse and children, who could then sponsor their parents, who could then sponsor their siblings, who could then sponsor their spouses and children. This “chain” operated independently of the business cycle or the assimilative capacity of the nation.

Additionally, for the first time in U.S. history, the 1965 Act imposed a cap on immigration from the Western Hemisphere (120,000 annually).22 This well-intentioned bureaucratic symmetry had the unintended consequence of criminalizing the traditional, circular flow of labor from Mexico, thereby creating the modern phenomenon of mass “illegal immigration”.23

60 Years Of Resuming A New “Great Wave”

The post-1965 era has been defined by the reversal of the gains made during the Great Pause. The return to mass immigration, coupled with a new ideology of multiculturalism, has strained the constitutional order and the social compact.

Demographic Transformation and the Rise of Multiculturalism

The foreign-born population exploded from its low of 4.7% in 1970 to nearly 14% today, returning to the unstable levels of the 1910s.24 However, unlike the 1920s, the post-1965 immigrants arrived in a country that had lost its will to assimilate them.

In the 1970s, the ideal of “Americanization” was replaced by multiculturalism and bilingualism.

- The Bilingual Education Act of 1968 and the Supreme Court’s decision in Lau v. Nichols (1974) institutionalized the preservation of foreign languages in public schools, removing the imperative for rapid English acquisition.25

- Identity politics encouraged newcomers to view themselves as members of aggrieved racial or ethnic groups rather than as aspiring individuals joining a constitutional republic.

Conservative intellectual John O’Sullivan termed this the “National Question”: whether the U.S. is a distinct nation with a specific culture to be preserved, or merely a geographic space for a collection of diverse tribes.27 The shift from the “melting pot” to the “salad bowl” has fundamentally altered the social fabric.

The Erosion of Social Trust

The consequences of this diversity without assimilation were empirically documented by Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam. In his landmark study E Pluribus Unum, Putnam found a strong negative correlation between diversity and social trust. In diverse communities, residents “hunker down”: they trust their neighbors less, vote less, give less to charity, and have fewer friendhttps://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/publications/e-pluribus-unum-diversity-and-community-in-the-twenty-first-centu/s.28

For the constitutional conservative, social trust is the currency of limited government. When trust is high, communities police themselves and civil society flourishes. When trust evaporates, the state must step in to mediate conflicts and redistribute resources. Thus, mass immigration acts as a solvent on the bonds of voluntary association that make liberty possible.

The Welfare State vs. The Nation State

Finally, the post-1965 era confirmed Milton Friedman’s famous warning: “You cannot simultaneously have free immigration and a welfare state”.29

The immigrants of the Great Wave arrived in a laissez-faire America with no safety net. If they did not work, they did not eat. The post-1965 wave arrived in a developed welfare state. The presence of a large, low-skilled immigrant population has expanded the constituency for government assistance and redistribution. As the tax burden for public services (education, healthcare, infrastructure) grows to accommodate this population, the conservative project of fiscal responsibility becomes politically impossible.30

Furthermore, the expansion of government bureaucracy to manage diversity—from diversity officers in schools to the vast apparatus of the welfare state—correlates directly with the era of mass immigration. As the population becomes more heterogeneous and less cohesive, the government becomes more powerful and intrusive.

Conclusion: Restoring the Constitutional Order

The history of the United States between 1924 and 1965 offers a powerful, empirically grounded lesson for the present. It demonstrates that immigration is not a natural force to be endured, like the weather, but a public policy that must be managed in the national interest.

The “Great Pause” was not a mistake. It was a necessary act of nation-building that:

- Forged a unified people out of a fragmented population, fulfilling the preamble’s promise to “secure the Blessings of Liberty.”

- Created the black middle class by tightening labor markets and forcing capital to compete for domestic labor.

- Preserved the social conditions necessary for limited government and republican liberty.

The post-1965 experiment in mass, unassimilated immigration has unraveled these successes. It has stagnated wages for the working class, fractured our civic culture with identity politics, and fueled the endless growth of the administrative state.

For everyone living in the USA, the path forward is clear. This is NOT a policy only for conservatives. It’s a policy that puts the well-being of the United States of America at the forefront.

It is not “anti-immigrant” to insist on limits; it is pro-citizen. To preserve the Constitution, we must preserve the “one people” who ordained it. This requires a return to the wisdom of the Great Pause: a policy of moderate, selective immigration that prioritizes the economic interests of American workers and the cultural preservation of the American republic.

As we look to the future, we must remember that the “melting pot” is not a magic cauldron that works automatically. It requires heat, pressure, and above all, limits. Only by restoring the conditions of assimilation—controlled borders, distinct national identity, and the rule of law—can we ensure that the United States remains a unified nation of free citizens, rather than a fragmented administrative state of warring tribes.

Appendix A: Comparative Immigration Statistics

| Metric | The Great Pause (1924-1965) | The Post-1965 Era (1965-Present) |

| Policy Focus | Assimilation, Restriction, National Origins | Family Reunification, Diversity, Labor Importation |

| Average Annual Inflow | ~180,000 | ~1,000,000+ |

| Foreign-Born % (End) | 4.7% (1970) | 13.7% (2018) 24 |

| Black Wage Growth | +406% (1940-1970) | Stagnation/Decline relative to productivity |

| Assimilation Model | “Americanization” / Melting Pot | Multiculturalism / Salad Bowl |

| Social Trust Trend | Increasing (High cohesion) | Decreasing (Putnam’s “Hunkering Down”) |

(Note: All citations refer to the source material used to compile this report.)

Works cited

- Immigration-Pause-1924-1965-Report.pdf, http://mylibertyblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/the_immigration_pause_of_1924_until_1965.pdf

- accessed November 23, 2025, https://cis.org/Report/Rise-and-Fall-Immigration-Act-1924-Greek-Tragedy#:~:text=And%20the%20Act%20fostered%20a,men%20rose%20by%20406%20percent.

- Founding Fathers on immigration – The Martha’s Vineyard Times, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.mvtimes.com/2017/02/15/founding-fathers-immigration/

- A Brief History of U.S. Immigration Policy from the Colonial Period to the Present Day, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/brief-history-us-immigration-policy-colonial-period-present-day

- Immigration Advocates Must Consider Virtue, Not Just Economics – Cato Unbound, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.cato-unbound.org/2021/08/06/peter-skerry/immigration-advocates-must-consider-virtue-not-just-economics/

- Hamilton’s actual view on immigration – The Institute of World Politics, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.iwp.edu/articles/2016/12/21/hamiltons-actual-view-on-immigration/

- Chapter 2: The source and scope of the federal power to regulate immigration and naturalization, accessed November 23, 2025, https://hrlibrary.umn.edu/immigrationlaw/chapter2.html

- Official English Fosters the Patriotic Assimilation of Immigrants – Hudson Institute, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.hudson.org/domestic-policy/official-english-fosters-the-patriotic-assimilation-of-immigrants

- To “Possess the National Consciousness of an American” (Louis Brandeis, July 4, 1915), accessed November 23, 2025, https://cis.org/Possess-National-Consciousness-American-Louis-Brandeis-July-4-1915

- Americanization (immigration) – Wikipedia, accessed November 23, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Americanization_(immigration)

- A Century Later, Restrictive 1924 U.S. Immigration Law Has Reverberations in Immigration Debate – Migration Policy Institute, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/1924-us-immigration-act-history

- The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act) – Office of the Historian, accessed November 23, 2025, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act

- Immigration Act of 1924 – Wikipedia, accessed November 23, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immigration_Act_of_1924

- Immigration Act of 1924, accessed November 23, 2025, https://loveman.sdsu.edu/docs/1924ImmigrationAct.pdf

- We’re All in the Same Boat Now: Coolidge on Immigration, accessed November 23, 2025, https://coolidgefoundation.org/blog/were-all-in-the-same-boat-now-coolidge-on-immigration/

- NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CULTURAL ASSIMILATION DURING THE AGE OF MASS MIGRATION Ran Abramitzky Leah Platt Boustan Katherine Eri, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22381/w22381.pdf

- Assimilation by the Third Generation? Marital Choices of White Ethnics at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century – Brown University, accessed November 23, 2025, https://s4.ad.brown.edu/Projects/UTP2/HGISDoc/Articles%20for%201880%20page/Intermarriage%203rd%20generation.pdf

- The Hart-Celler Immigration Act of 1965, accessed November 23, 2025, https://cis.org/Report/HartCeller-Immigration-Act-1965

- The 1965 Immigration Act: Opening the Nation to Immigrants of Color, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/essays/1965-immigration-act-opening-nation-immigrants-color

- Three Decades of Mass Immigration: The Legacy of the 1965 Immigration Act | CUNY, accessed November 23, 2025, https://files.eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4886/2015/01/16060742/cis.org-Three_Decades_of_Mass_Immigration_The_Legacy_of_the_1965_Immigration_Act.pdf

- Fifty Years On, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act Continues to Reshape the United States – Migration Policy Institute, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/fifty-years-1965-immigration-and-nationality-act-continues-reshape-united-states

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 – Wikipedia, accessed November 23, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immigration_and_Nationality_Act_of_1965

- Unintended Consequences of US Immigration Policy: Explaining the Post-1965 Surge from Latin America – PubMed Central, accessed November 23, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3407978/

- Facts on U.S. immigrants, 2018 – Pew Research Center, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2020/08/20/facts-on-u-s-immigrants/

- Bilingual Education Act – Wikipedia, accessed November 23, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilingual_Education_Act

- Lau v. Nichols revisited: unveiling dual language program disparities in California for Asian students and marginalized communit, accessed November 23, 2025, https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1162&context=education_fac

- National Conservatism and Its Discontents – Claremont Review of Books, accessed November 23, 2025, https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/national-conservatism-and-its-discontents/

- E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century the 2006 johan skytte prize lecture – Research Explorer – The University of Manchester, accessed November 23, 2025, https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/publications/e-pluribus-unum-diversity-and-community-in-the-twenty-first-centu/

- Look to Milton: Open borders and the welfare state | The Heritage Foundation, accessed November 23, 2025, https://www.heritage.org/immigration/commentary/look-milton-open-borders-and-the-welfare-state

The political economy of immigration and welfare state effort: evidence from Europe – Scholarly Publications Leiden University, accessed November 23, 2025, https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2911553/view